The “Giant Baby” Who Made Headlines Before Stardom

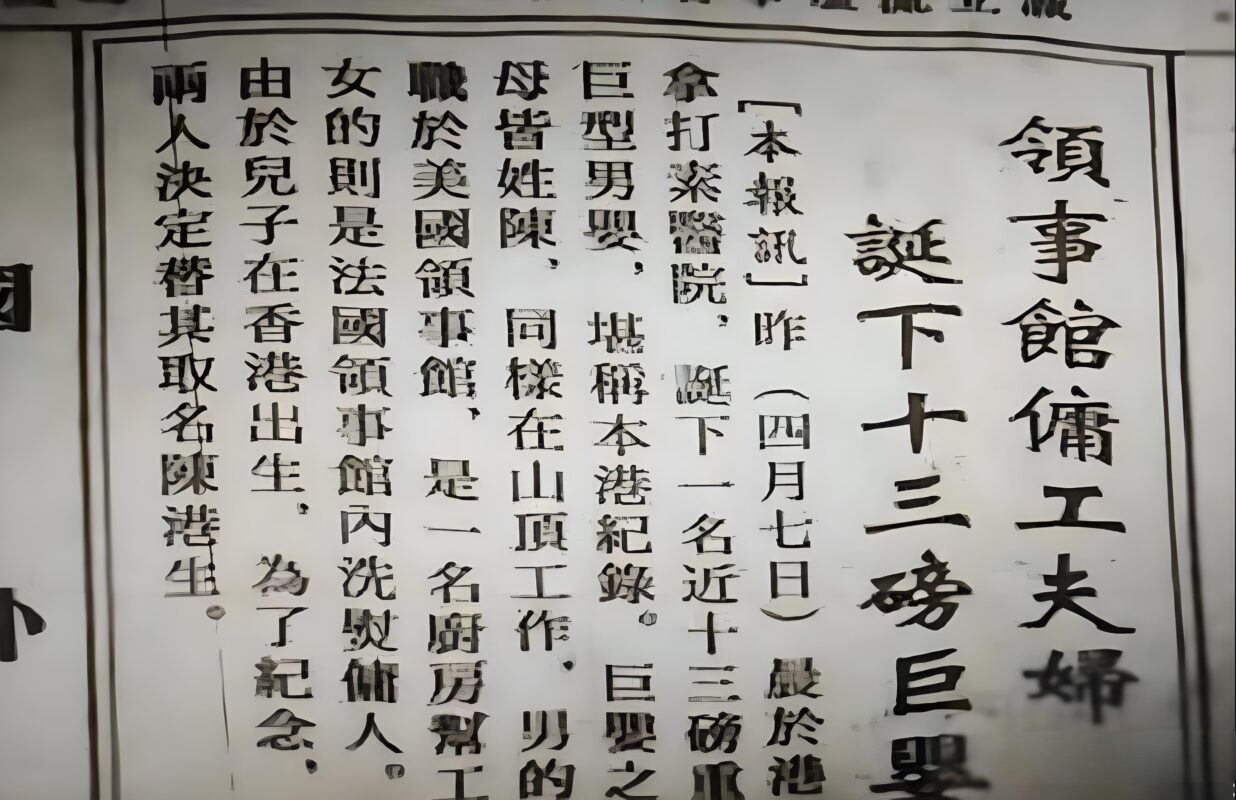

On April 7, 1954, Hong Kong’s Queen Mary Hospital witnessed an extraordinary birth: a newborn boy weighing 13 pounds (5.9 kg)—nearly double the average infant’s weight. Dubbed the “Century Giant Baby” by stunned medical staff, this child (later named Chan Kong-sang, meaning “Born in Hong Kong”) made front-page news in the Hong Kong Industrial and Commercial Daily before he could even open his eyes. The headline “Hong Kong’s Giant Infant” marked his accidental “debut” in the public eye—an ironic prelude to a life destined for global fame.

Medical professionals noted this was no ordinary birth. Classified as a “macrosomic birth” (infants over 8 pounds), Chan’s size defied 1950s medical norms. Nurses observed his unusually powerful limbs and thunderous cries, with one quipping, “This boy will either grow up to beat people or be beaten.” Decades later, this offhand prophecy crystallized: Chan would master both delivering explosive strikes in Drunken Master and enduring brutal falls in Police Story—a testament to his unique duality as a performer.

From Peking Opera Discipline to Silver Screen Innovation

The Crucible of “Seven Little Fortunes”

At age six, Chan’s restless energy led his parents to enroll him in Master Yu Jim-yuen’s China Drama Academy, a grueling Peking Opera school. As the youngest of the “Seven Little Fortunes” troupe, his days began at 5 AM with punishing drills: somersaults, splits, and handstands. Ironically, instructors criticized his “ox-like clumsiness” compared to agile peers like Yuen Biao. Yet this perceived limitation birthed his signature style—merging operatic grace with brute-force physicality.

The Stuntman’s Crucible

Post-graduation at 17, Chan became a $5-a-day stuntman at Shaw Brothers Studio. His early roles were anonymous sacrifices:

- The nameless thug kicked through a window by Bruce Lee in Fist of Fury (1972)

- The first henchman smashed in the opening brawl of Enter the Dragon (1973)

Dubbed “The Durable Big Guy” by crews, these years forged his kinesthetic intelligence—learning how falls looked on camera versus how they felt. Director Lo Wei’s attempt to rebrand him as “Jackie Chan” (meaning “Become the Dragon,” i.e., the next Bruce Lee) initially backfired. Only with 1978’s Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and Drunken Master did Chan break free, injecting Peking Opera clowning into fight choreography to pioneer kung fu comedy.

The Anatomy of a Human Dynamo: Physiology Meets Philosophy

Born for Impact

Modern kinesiology reveals why Chan’s body defied limits:

- High bone density from birth, reducing fracture risk

- Hypertrophic muscle fibers enabling explosive power

- Proprioceptive genius for spatial control during falls

A 2016 UCLA study confirmed infants over 9 pounds show 30% higher athletic aptitude—a theory Chan validated by performing a volcano descent on rollerblades at 57 (CZ12) and executing complex fight takes at 62 (The Foreigner).

The “No Romance” Doctrine

Chan’s career obsession bordered on ruthlessness. When wife Joan Lin was pregnant in 1982, he skipped prenatal appointments to film Project A’s infamous 15-meter clocktower fall—a stunt requiring three spinal realignments between takes. During Armour of God (1986), a 12-meter tree-branch fall fractured his skull, yet he returned within weeks to reshoot. This sacrificial ethos stemmed from Peking Opera’s creed: “The show eclipses heaven itself.”

From Concrete Floors to Oscar Gold: The Weight of Legacy

The hospital scale that read 13 pounds in 1954 now counterweights Chan’s Lifetime Achievement Oscar (2016). His journey embodies three transformative truths:

- Biology as destiny—His unique physique enabled stunts that broke 19 bones

- Tradition as innovation—Peking Opera’s fan shen (翻跟头) rolls evolved into Rush Hour’s ladder fights

- Pain as pedagogy—Every injury (e.g., Who Am I?’s 21-story slide) refined his “safe danger” choreography

In his memoir, Chan reframed his legacy: “My greatest stunt isn’t jumping from heights—it’s never stopping.” From Queen Mary’s maternity ward to Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre, he transformed 13 pounds of infant weight into six decades of cinematic gravity—proving that miracles aren’t born, they’re built, one shattered bone at a time.